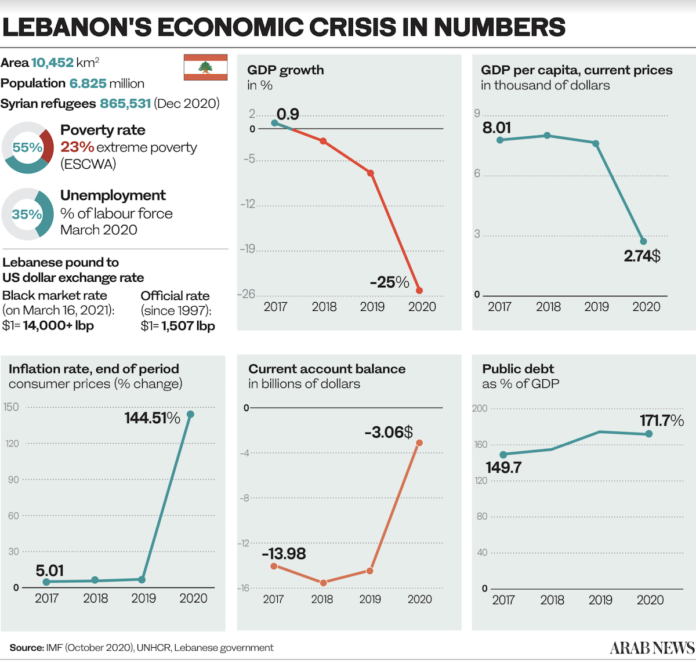

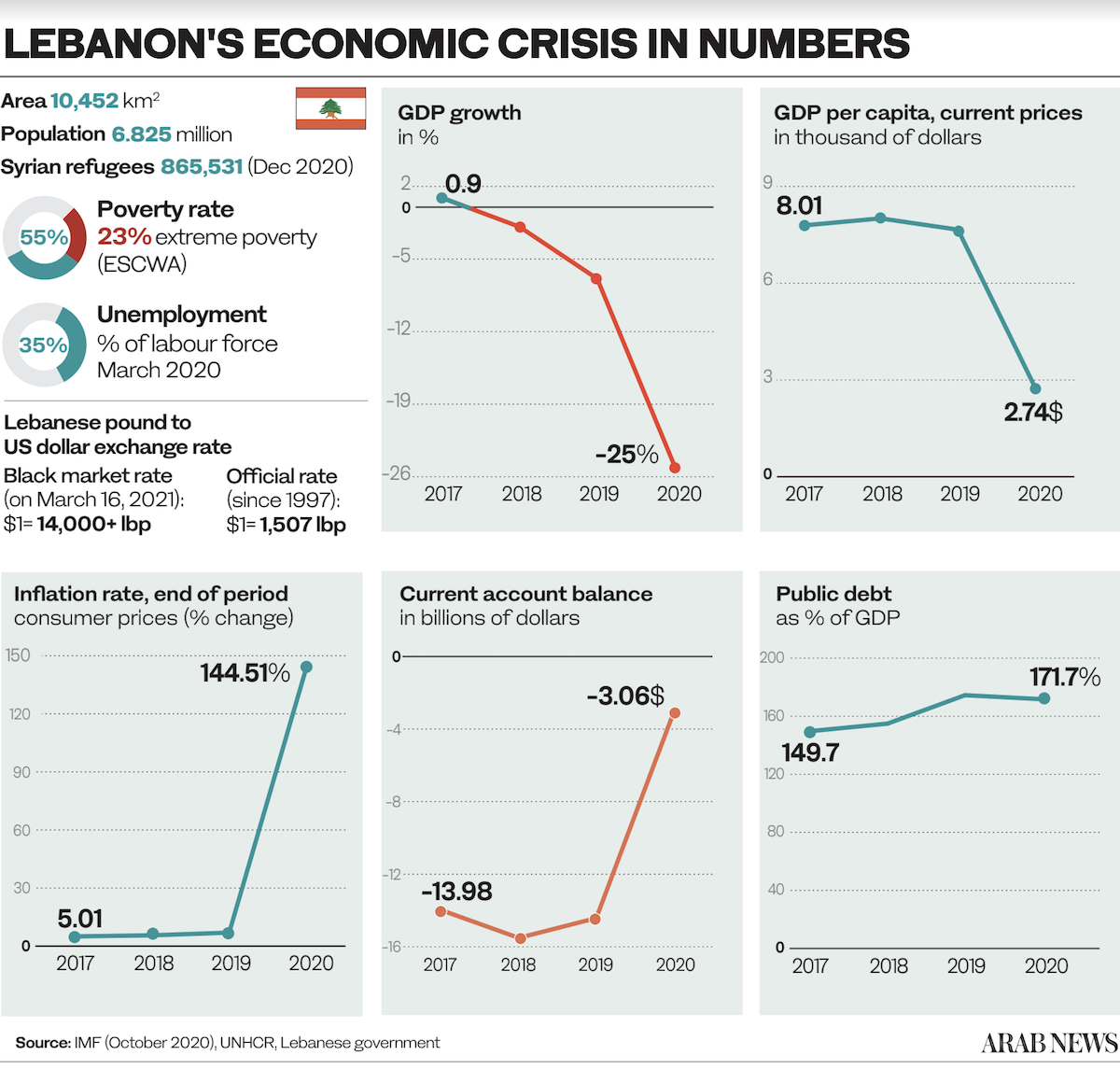

LONDON: Over the past two weeks the Lebanese pound has lost more than 20 percent of its value against the dollar on the black market. Since October 2019 the exchange rate has plummeted by 90 percent, affecting everyone in the country.

These numbers are stark. On March 16 three money changers told the AFP news agency they were buying dollars for 14,800 to 14,900 Lebanese pounds.

The currency is pegged to the dollar and the official rate is set at 1,507.5 pounds to one dollar. However, dollars are generally unavailable at the official rate because of the economic crisis, which is why black-market rates apply.

In 2020, Lebanon was the fourth most-indebted country in the world behind Japan, Greece and Eritrea. In March last year, the country defaulted on its international debt for the first time in its history. Since then, there have been no economic reforms and no payment plans agreed.

The situation is exacerbated by the banking crisis and the effects of the pandemic. The nation’s banks face bankruptcy, having lent up to 70 percent of their assets to an insolvent state and central bank. The country has lost its creditworthiness and is resorting to printing more, increasingly worthless, money which is further fueling inflation.

The depreciation of the pound resulted in staggering inflation of 84 percent in 2020. To make matters worse, food inflation stood at 402 percent. Meanwhile Lebanon’s gross domestic product contracted by 25 percent last year.

The World Bank estimates that 50 percent of Lebanon’s population has slipped below the poverty line, which is mind-boggling in a country that 60 years ago was known as the “Switzerland of the Middle East.”

The economic situation is worse now than it was during the civil war in the 1970s and 1980s.

What we see in Lebanon is a classic vicious circle: the worse the economy gets, the more the currency depreciates and vice versa. The numbers reflect a defunct economy.

The situation was already bad before the devastating explosion on Aug. 4 last year that destroyed Beirut’s port and a large section of the city. Since then, the nation’s economy has slid even further down the precipice.

The country is literally running out of money. Foreign reserves have dwindled from about $30 billion a year ago to about $16 billion, of which only between $1 billion and $1.5 billion is available to subsidize food and fuel imports.

These reserves are important because the central bank essentially subsidizes wheat, medicine and fuel prices by providing importers with hard currency at the official exchange rate.

Given the dwindling foreign reserves, interim finance minister Ghazi Wazni announced on Tuesday that subsidies will be removed from several non-essential products, such as cashew nuts and branded coffee. Gasoline subsidies will be reduced from 90 percent to 85 percent.

All of these financial pressures are hitting people in Lebanon hard and the situation is not going to improve any time soon. The government expects inflation to reach 77 percent this year — and that estimate was made before the removal of the aforementioned subsidies.

The more the currency depreciates, the further out of control inflation will spiral. A $246 million loan from the World Bank to support the 786,000 poorest people in the country is but a drop in the ocean, as is the 1 million pounds a month the government wants to give to the poorest families.

The Lebanese government has so far been largely inactive as it faces an unprecedented economic crisis. Wazni has announced that he wants to impose a 1 percent tax on bank deposits above $1 million, and charge 10 to 30 percent on the interest banks earn from deposits with the central bank.

These proposals will go down like a lead balloon in the face of banks and depositors who have already faced de facto haircuts on their deposits of more than 60 percent.

What we see in Lebanon is a classic vicious circle: the worse the economy gets, the more the currency depreciates and vice versa. The numbers reflect a defunct economy.

Cornelia Meyer

The government’s plan to devalue the currency and work toward a flexible exchange rate, while laudable, can only work in conjunction with a full program of economic reforms, which will have to be supported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the sake of credibility.

The situation grew so dire a week ago that President Michel Aoun tried to crack down on the ever-declining black market exchange rate by ordering security forces to intervene when the exchange rate exceeded 10,000 pounds.

He justified his order by highlighting the “dangerous repercussions” the deteriorating exchange rate is having “on social security.”

His speech could not halt the slide of the currency, and neither could his security forces. Hassan Diab, the country’s caretaker prime minister, also warned this month that Lebanon could slide deeper into chaos amid the exchange rate’s continuing nose dive.

Angry protesters blocked highways and streets, outraged by political inaction and corruption in the face of untold economic suffering.

A comprehensive plan for economic reforms and a bailout from the IMF are vital if confidence in the Lebanese economy is to be restored. The reforms required by the IMF will come at a price, and politicians will need to be willing to explain that to the general population.

This will not be an easy task, especially given the Lebanese people have already endured enormous economic hardship, which means opposition to further suffering is inevitable.

Whichever way we look at Lebanon’s economic woes, they cannot be divorced from the nation’s politics. The country needs a government that can be a counterparty with which international institutions and bilateral lenders can negotiate.

The political arena in Lebanon is complex, with sectarian and geopolitical undertones that have their origins in the civil war and the geopolitical complexities of the regional neighborhood, including the influence of Iran and Hezbollah.

The caretaker government, which is headed by a prime minister who has wanted to resign for a long time and does not have a mandate to negotiate with the IMF, will be incapable of convincing the population to accept what will doubtlessly be the draconian measures required as part and parcel of any agreement with the lender.

The US, France and the UK have made it clear that they are prepared to support a competent, reform-minded Lebanese government, but are not willing to fund defunct political classes who seem unwilling to form a government.

In other words, the IMF needs a partner with whom it can negotiate a comprehensive program of reforms in exchange for a bailout package.

The IMF will also demand, as a precondition for any engagement, a comprehensive audit of the Banque du Liban, Lebanon’s central bank, which will be an uncomfortable prospect for some in the political class.

There is no way out of the nation’s economic downward spiral, and the endless and uncontrolled devaluation of its currency, without an agenda that includes wide-ranging economic and tax reforms.

As long as those in power in Lebanon remain reluctant to show a will to implement such reforms, the IMF’s hands are tied and Western allies such as the US, France and the UK will not help.

———————

* Cornelia Meyer is a Ph.D.-level economist with 30 years of experience in investment banking and industry. She is chairperson and CEO of business consultancy Meyer Resources. Twitter: @MeyerResources

Freefalling Lebanon currency hits new lowHariri promises new Lebanon government soon after clear-the-air talks with Aoun