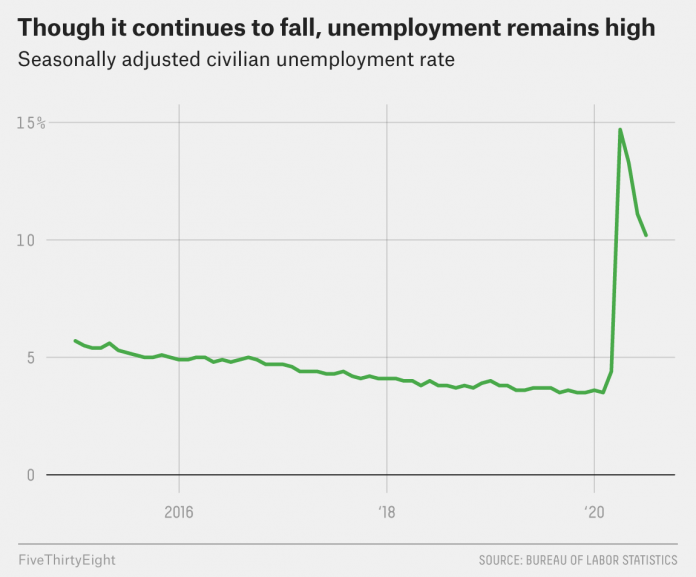

After three straight months of declining unemployment, we have only just returned to levels of unemployment that rival the depths of the Great Recession. Friday’s jobs report revealed that the unemployment rate dropped from 11.1 percent in June to 10.2 percent in July, and 1.8 million more people were employed in July than in June.

So the economic recovery is continuing — but it’s moving very slowly, and we aren’t close to being out of the woods. Still, this report could have been much worse. After all, weekly unemployment claims rose a bit in July after falling for 15 straight weeks since late March. And across the country, phased reopenings have been rolled back over the past month as the number of COVID-19 infections spiked, preventing more workers from coming back to their jobs.

But the unemployment rate isn’t exactly dropping at the rate you’d expect for an economy that’s roaring back to life: The improvement from June to July was less than half as large as the one from May to June. And if the economy’s momentum is slowing, that means the recovery could be long and painful — particularly if Congress, which is currently deadlocked over the next round of coronavirus relief, cuts back on the aid it’s been pouring into the economy since March.

The economy has now regained about 9 million jobs since April, at which point more than 21 million jobs were lost. The unemployment rate has also fallen substantially from an official peak of 14.7 percent in April — which in reality was likely closer to 20 percent, thanks to a misclassification error on one of the surveys used to produce the jobs report that the Bureau of Labor Statistics now seems to have mostly under control.

One clear message of this month’s jobs report is that the recent uptick in nationwide COVID-19 infections doesn’t seem to be reversing the economic recovery. That runs somewhat contrary to the mixed economic signals we’ve been getting over the past few weeks: In addition to rising weekly unemployment claims, GDP growth was historically dismal for the second quarter of the year — down an annualized rate of 32.9 percent. That, combined with a report from the payroll processing company ADP which showed a substantial slowdown in hiring in July, was enough to spur speculation that the economy might already be backsliding, as gains in consumer spending stalled and businesses across the country were forced to scale back operations only a few weeks after states’ phased reopenings went into effect.

And according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s weekly pulse survey, the share of people who expected someone in their household to lose employment income rose from under 32 percent in early June to 35 percent in early July, after having dropped each week from the beginning of May. That seemed like it might be a leading indicator for unemployment, since it’s measuring anxiety in the workforce before actual job losses occur.

But although those trends might seem at odds with the data in today’s report, they’re a much more imperfect gauge of the state of the economy. Though they come out much more frequently than the monthly jobs report, weekly claims aren’t necessarily reflective of job losses as they’re happening. It’s possible that some of the fluctuations in weekly claims aren’t that meaningful at this point, since the numbers are so huge.

Meanwhile, not all of the real-time economic data we’ve seen recently has been bad. For instance, data from job-search websites such as Indeed shows that job postings have steadily trended upwards since dropping massively in April. At the beginning of May, job postings were down nearly 40 percent relative to the same week in 2019, but are now down just 18 percent compared with last year. We’d expect that improvement to be associated with a decrease in unemployment rate since May — particularly since the gains in postings have been almost uniformly steady.

As you dive deeper into this month’s report, some surprising trends emerge. Since it’s Friday, we’ll start with the good news first: permanent layoffs didn’t grow substantially and more people who lost their jobs temporarily seem to be finding work. In July, 76 percent of jobless workers were on temporary layoff while 24 percent had lost their jobs permanently. That’s slightly higher than in June, when 21 percent of layoffs were permanent, and much higher than the 10 percent share in April. But on the whole, permanent unemployment didn’t increase — a promising sign, since it’s much harder for workers to get back into the labor force if their former employer has cut ties with them completely.

In terms of industries, all of the major economic sectors we’ve been tracking throughout the recovery continued to gain jobs in July:

Jobs still haven’t caught up to pre-crisis levels yet

Net change in total employment over various time frames, by sector

| Net Change In Employment Over Last… | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry sector | 1 Month | 3 Months | 6 Months |

| Construction | +20,000 | +639,000 | -398,000 |

| Education and health services | +215,000 | +1,170,000 | -1,559,000 |

| Leisure and hospitality | +592,000 | +3,978,000 | -4,281,000 |

| Professional and business services | +170,000 | +648,000 | -1,621,000 |

| Retail trade | +258,300 | +1,471,100 | -910,300 |

| Transportation and warehousing | +37,900 | +99,800 | -470,300 |

These are encouraging numbers for some of the areas hit hardest by coronavirus-related shutdowns in the spring, though we should remember that none of them are close to regaining their pre-crisis employment levels. Leisure and hospitality, for instance, is still down 4.3 million total jobs over the past six months, despite the huge recent gains. And as infections remain at dangerously high levels across the country, it could be increasingly difficult for bars, restaurants, hotels and other businesses in this category to continue their rapid employment gains.

And while state and local governments gained nearly 300,000 jobs last month as well, it could be mostly a mirage. Almost all of those gains were in education, and that’s where we may run into problems with the way the BLS’s seasonal adjustments — which follow the ebb and flow of employment under normal circumstances — account for monthly changes. The issue this month is that many teachers were laid off earlier than usual this summer, which may have artificially inflated July’s jobs numbers.

Women — who have been hit harder than men during this recession — did see some substantial gains this month. Their unemployment rate fell from 11.7 percent in June to 10.6 percent in July. The unemployment rate for Hispanic or Latino workers, which hit a peak of nearly 19 percent in April, was at 12.9 percent this month, too — which is a big improvement.

But while nearly every demographic group saw its economic prospects improve in July, some of the most vulnerable workers are still being left behind. There was barely any improvement (less than a percentage point) in the unemployment rate for Black workers, which is still the highest of any racial and ethnic group, at 14.6 percent. Black or African American women have experienced a particularly slow drop in unemployment; July saw their unemployment rate fall by only 0.6 percentage points.

And all of these gains were made possible — at least in part — by the enormous amount of money the federal government has pumped into the economy since March, some of which is already starting to expire. For instance, people kept spending money, despite high levels of unemployment, because the federal government was keeping jobless workers afloat with an additional $600 per week in benefits. No one is getting that $600 payment right now, though, since it expired at the end of July and Congress is still deadlocked over whether to extend it. And without more stimulus money to buoy consumer spending — not to mention additional funds from a federal program that’s helped small businesses keep or bring workers back onto their payrolls — businesses could struggle in the future to keep workers on the job.

Meanwhile, Nick Bunker, the director of economic research for North America at the Indeed Hiring Lab, a research institute connected to the job-search site Indeed, pointed out that so far, we’re not seeing anything close to a v-shaped recovery, which some of President Trump’s advisers have continued to confidently predict.

“It’s important to remember that this is where we are after several months of bounce back and an unprecedented amount of fiscal stimulus,” Bunker said. But further gains will be more and more difficult, especially if an increasing number of temporary layoffs become permanent.

If anything, he said, the falling unemployment rate is a sign that the government’s investment in the economy is working — not that it’s time to turn off the money tap. “No one should be thinking ‘mission accomplished’ right now,” Bunker said.