WASHINGTON (AP) — As the first round of COVID-19 vaccinations trickled out across the United States, many members of Congress lined up at the Capitol physician’s office to get inoculated.

President-elect Joe Biden got vaccinated, too, as did Vice President Mike Pence. Both rolled up their sleeves live on television to receive their shots.

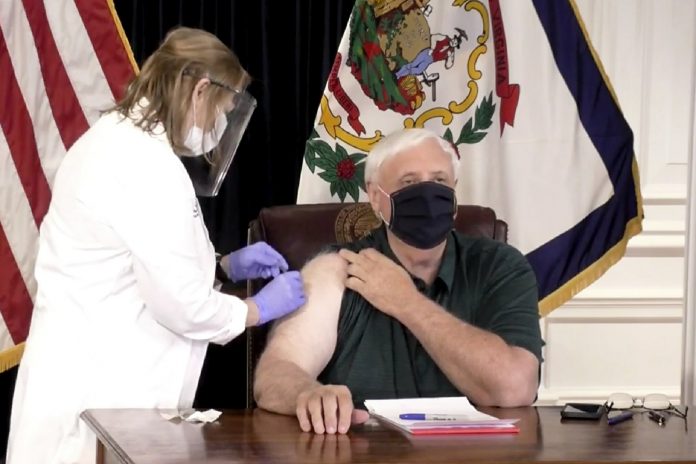

For some of America’s political leaders, there are practical imperatives for getting vaccinated early: their own risk factors, ensuring continuity at the highest reaches of the U.S. government and helping build public confidence in the vaccine. But there are also tricky optics for politicians to navigate, particularly with supplies of the vaccines still exceedingly limited and millions of elderly Americans and essential workers weeks away from being inoculated.

“We want to ensure that everyone feels safe about this vaccine and sees some of the more prominent members of society getting it, but also ensure people don’t say ‘what about us?’” said Utibe R. Essien, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

With the pandemic raging across the country, and more than 320,000 Americans already dead, some lawmakers with access to the vaccine said they were indeed planning to wait until more Americans could get their shots before getting theirs.

“I intend to take the vaccine,” tweeted Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, a Republican. “But, because I’m healthy & relatively young, I’m going to wait until seniors & frontline workers have the opportunity to take it first.”

Minnesota Rep. Ilhan Omar, a liberal Democrat who lost her father to the virus, tweeted that it was “disturbing to see members be 1st to get vaccine while most frontline workers, elderly and infirm in our districts, wait.”

The debate over politicians’ access to the vaccine is relatively specific to the United States. Though a handful of foreign leaders, like Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, have gotten publicly vaccinated, many have refrained.

In Canada, for example, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said he has no problem waiting for his shot.

“When there’s a time for healthy people in their 40s to get their vaccine, when it’s our turn, I will be as close to the front of that line as I can get,” Trudeau told CP24 television. “I am super enthusiastic about getting vaccines, and I certainly want to show people that they’re safe and that we trust our doctors, but there’s a lot of vulnerable people who need to get these vaccines much quicker than I will, and we’re going to make sure that they get it first, because that’s the priority.”

Canadian historian Robert Bothwell said there’s less of an imperative in his country for political leaders to get the vaccine because they don’t face the same skepticism of public health guidance as in the U.S.

“Canadians have trusted more in government,” Bothwell said.

Indeed, the pandemic and the guidance of health authorities in the U.S. has gotten tied up in the nation’s broader partisan divides. Democrats have lauded public health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci, who called for tight restrictions to slow the spread of the virus, while some Republicans chafed against those same measures.

There are also real concerns that many Americans will be skeptical about taking the vaccines, which were developed and approved far faster than any previous vaccines. An Associated Press-NORC poll conducted earlier this year, before the FDA approved vaccines from pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and Moderna, found only half the U.S. population planned to get vaccinated.

“I’m hopeful that people say ’this senator got vaccinated, this congressman got vaccinated, and I may not trust the public health system but I trust them,” Essien said. “The messenger has to be different.”

The politicians lining up to get vaccinated in the U.S. cross the political spectrum.

Virginia Rep. Don Beyer, a Democrat who was one of the first in line for his shot, said: “Millions of Americans are waiting for shots, many of whom are workers on the front lines of this pandemic. I am not more important than they are, but national leaders must lead by example.”

Several conservatives, who have been more likely to oppose strict pandemic control measures, cast the vaccinations as a necessary step toward getting Americans back to work and stabilizing small businesses. Texas Rep. Mike McCaul, a Republican, said in a video after receiving the vaccine that it will “get our economy back on track to support hard-working Americans.”

Some Democrats, however, have cried foul over Republicans who did not follow earlier public health guidelines getting vaccinated before many Americans who did.

“It’s interesting to watch my GOP colleagues who refused to wear a mask or practice social distancing, and who attended ‘super spreader’ events, jump in line to get vaccinated. Shameless,” Florida Rep. Val Demmings said.

Public experts, however, have warned that access to the vaccines shouldn’t be tied to past actions. And some said it was okay to make politicians a priority for inoculation, given the crucial work the government needs to do to address the impact of the pandemic and other tasks.

“It’s important for our government to be functioning well,” said Ashish Jha, dean of Brown University’s school of public health. “We don’t want to risk governors and members of Congress getting sick and dying.”

Still, Minnesota State Sen. Matt Klein worries politicians will end up regretting early inoculation. He himself just got his shot, but not due to his legislative position. Klein is a doctor who treats COVID-19 patients at a Minneapolis-area hospital.

“Honestly, it should be front-line people,” Klein, a Democrat, said. “I understand that a lot of the politicians are getting it to demonstrate to the public that it’s safe, but I’m afraid it will instead generate resentment.”

—-

Piper Hudspeth Blackburn in Frankfort, Kentucky, Kimberly Chandler in Montgomery, Alabama, West Virginia, Josef Federman in Jerusalem, Rob Gillies in Toronto and Cuniyt Dil and Mary Clare Jalonick in Washington contributed to this report.